Male cats can easily develop obstruction of the urethra which is the tube draining urine from the bladder out of the penis. Obstructions are often the result of plugs of inflammatory material, mucus, crystals, small stones (called calculi) that have formed in the kidneys and have passed down into the bladder (see urinary stones). The cause of the inflammatory materials and stone formation it not well understood, though viral infections and diet may play a role. Other causes are reported such as cancer, previous injury causing scarring, and trauma are also reported. Early neutering of cats does not cause reduction of urethral size as in some other species.

Most affected cats are within 1 to 10 years of age. Signs and symptoms may vary from mild to severe. Initially cats may show signs of urinary tract inflammation and discomfort, including straining to urinate, frequent urination, blood in the urine, painful urination, and inappropriate urination (urinating outside of a litter box).

These bouts can resolve in 5–7 days but recur in many cats within 6–12 months. Symptoms are profound and life threatening if complete obstruction occurs and no urine can get out of the body. Once cats become completely obstructed, they may attempt to urinate in the litter box but will produce no urine. The cat may cry, move restlessly, or hide because of discomfort, and eventually lose their appetite and become lethargic. Complete obstruction can cause death of the cat in 3–6 days. A cat with a urethral obstruction will have a large, painful bladder that is easily felt in the back half of the belly unless the bladder has ruptured.

Some risk factors have been evaluated for lower urinary tract disease in cats. Increased risk was found in cats that eat dry food, being kept indoors, nervous/fearful/aggressive behaviors, stress, and being in multi-cat household. The incidence of urinary obstructions is reportedly higher in the winter months. Bladder inflammation leading to mucous plugs (sometimes called “Feline Urologic Syndrome” or “FUS”) is more common in male cats. Congenital outpouchings of the bladder (“vesicourachal diverticuli”) can increase the risk of bladder infection, but they may also be a result of chronic inflammation.

In cats with signs of urinary tract inflammation, blood work is evaluated to check kidney function and to determine if there is any evidence of infection or other systemic illnesses. A urine sample is evaluated for crystals and may be sent in for culture, although bacterial infections of the bladder are uncommon in cats. In cats with recurrent infections, x-rays of the belly may be taken to see if calculi (stones) or other material are present in the kidneys or bladder (Figure 1), and your primary care veterinarian may inject contrast material into the bladder during x-rays to see if there are any anatomic causes for straining and bloody urine, such as a bladder wall defect or a stricture (narrowing) of the urethra.

Cats that have urinary obstruction require emergency treatment. Sedation or general anesthesia is needed in all but the sickest patients to allow placement of a catheter into the urethra to flush out the plug or force the stone into the bladder. The bladder is thoroughly flushed and drained through the catheter to remove any remaining sediment. The urinary catheter is then typically left in place for a few days until urethral swelling subsides. Once the catheter is removed, the cat is then evaluated to make sure he/she can urinate freely before being discharged from the hospital. Your veterinarian may also prescribe pain medication, a diet change to decrease crystal-forming tendency, or other drugs to make the cat more comfortable and help he/she to relax.

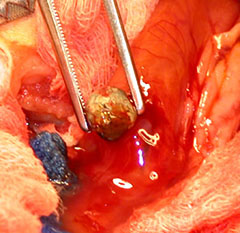

In cats with bladder stones that can be flushed into the bladder, a cystotomy (surgical opening of the bladder) is performed to remove the stones (Figure 2). Cystotomy is also performed in cats with congenital outpouchings of the bladder (“vesicourachal divericuli”).

If the obstruction recurs or cannot be relieved, a thorough work-up (including x-rays, cultures, and contrast studies of the bladder and urethra) should be performed before surgery is considered.

If your cat has multiple occurrences that cannot be unblocked or managed medically, and does not have any underlying conditions that could cause recurrence, your veterinarian may recommend a perineal urethrostomy (“PU”), or surgical widening of the urethra. (Figure 2) This procedure is intending to provide a permanent opening that allows crystals, mucus plugs, or small stones to pass out of the urethra; this minimizes the chance of re-obstruction.

Pelleted or paper litter may be used for several days after the surgery. Cats that have severe swelling or leakage of urine under the skin may require placement of a urinary catheter for 2–3 days. An Elizabethan collar is kept on the cat for 10–14 days after surgery to prevent self-trauma which is devastating to the outcome of the surgery. In some cats, absorbable sutures are used in the surgery site, while other cats may have nonabsorbable sutures that require removal in 10–14 days. Cats should be rechecked at regular intervals after the surgery.

After surgery, some cats will develop bleeding or swelling. Stricture (scarring and narrowing) of the urethrostomy site may occur if the cat traumatizes the surgery site or with incomplete dissection or urine leakage under the skin (Figure 3). This can cause recurrence of symptoms or complete blockage. Bacterial urinary tract infections occur in 25% of cats within the first year after perineal urethrostomy. Perineal urethrostomy does not prevent bladder inflammation or stone formation.

Prevention of urethral blockage depends on the cause of the blockage. If the surgery is performed properly, it is unlikely that cats will develop subsequent urinary obstructions. Perineal urethrostomy does not prevent bladder inflammation or stone formation, however, so clinical signs of urinary tract disease may continue in some cats.