Chylothorax, characterized by the accumulation of chyle within the thoracic cavity, is a relatively uncommon disease that affects dogs and cats. Chyle has a characteristic milky appearance (Figure 1) and it contains small molecules of fat. After eating, food is digested by your pet and the fatty component of the meal is further broken down into small molecules termed chylomicrons. The intestinal lymphatic system that travels to a structure called the cisterna chyli (CC), which is located in the front portion of the abdomen, near the kidneys, absorbs these small molecules. The CC is a lymphatic reservoir that receives chyle from the intestine but also receives lymphatic fluid from the rest of the abdomen and pelvic limbs. The thoracic duct (TD) is the extension of the CC into the chest, which carries chyle into the thoracic cavity and eventually empties its contents into the cranial vena cava (CrVC) close to the heart (Figure 2). In pets affected with chylothorax there is an abnormality in the TD that causes it to leak chyle into the thoracic cavity. These pets have difficulty breathing as the chyle that builds up in the chest prevents their lungs from fully inflating with air. The lymphatic fluid that is also a main component of chyle contains protein, white blood cells, and vitamins. The loss of large amounts of chyle into the thorax can weaken your pet’s immune system and create severe metabolic disorders. Chyle is also an irritant and chronic exposure to the lining of the lungs (pleura) and heart (pericardium) can lead to inflammation of those surfaces with further deleterious consequences.

Any disease process that obstructs or impedes the outflow of chyle from the TD into the CrVC can potentially lead to chylothorax. Cancer, fungal disease, heart disease, and blood clots within the CrVC have all been reported as causes of chylothorax in dogs and cats. It is suspected that all of these diseases prevent normal outflow of chyle from the TD into the CrVC. As a result, chyle backs up into the TD and eventually leaks out into the thoracic cavity. Ultimately, in veterinary patients, an underlying cause is rarely found and chylothorax is deemed idiopathic, or of unknown origin.

The clinical signs that a pet with chylothorax displays are not specific to the accumulation of chyle in the thorax since any substance (blood, air, pus) that impedes lung expansion can cause breathing difficulties. Your pet may develop a non-productive cough or breathing difficulties. With the loss of large amounts of chyle into the thorax, your pet can lose vital nutrients and they can become lethargic or lose their appetite. Weight loss can also occur over a period of time. Should you notice any of these signs, your pet should be evaluated by your primary care veterinarian.

The first thing your veterinarian will perform when they evaluate your pet is a physical examination. Auscultation of the thorax may reveal reduced or muffled heart and lung sounds as a result of the fluid in the thoracic cavity. A heart murmur, if detected, is an important finding as heart disease is a possible cause of chylothorax.

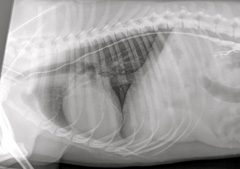

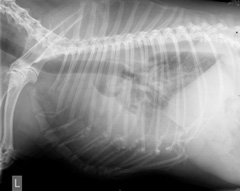

If there is a suspicion of fluid in the thoracic cavity (pleural effusion) often the first diagnostic test performed is radiographs. Radiographs can only confirm the presence of fluid in the thorax and cannot provide a diagnosis of chylothorax (Figure 3).

After confirming pleural effusion, obtain a sample of the fluid to characterize the disease process further. Sampling of thoracic fluid (thoracocentesis) is performed by placing a small gauge needle into the thoracic cavity and aspirating until fluid is obtained. This is a relatively uncomplicated procedure; however, it may be necessary to sedate your pet. If thoracocentesis obtains a milky fluid, chylothorax can be highly suspected. An example of chylous pleural effusion obtained from a thoracocentesis is shown above (Figure 1). Your veterinarian will likely submit a sample of the fluid along with a blood sample to a laboratory for confirmation of chylothorax.

All potential underlying causes of chylothorax should be investigated. Your veterinarian may recommend having a cardiac and thoracic ultrasound or even a computed tomographic (CT) scan performed on your pet to determine if there is heart disease or thoracic cancer that could lead to chylothorax. These tests are much more sensitive compared with radiographs.

Remember that in most cases an underlying cause of chylothorax is usually not identified.

Medical management of chylothorax involves evacuation of chyle from the thorax, either with a tube placed in the chest or intermittent thoracocentesis. If a tube is placed in your pet’s chest they will need to be hospitalized. The purpose of thoracic fluid evacuation is to allow the lungs to fully expand, relieving any breathing difficulty or coughing, making your pet much more comfortable. Feeding your pet a low-fat diet has been recommended to reduce the fat content of chyle and; therefore, reduce the flow of chyle through the TD. However, based on previous reports, it is unlikely that a low-fat diet alone will reduce the volume of chyle flowing through the TD. A nutriceutical called rutin may be a useful oral supplement in pets with idiopathic chylothorax. Rutin is available over-the-counter at most specialty health food stores and it is suspected that rutin stimulates protein breakdown and removal in lymphatic vessels. The efficacy of rutin in the treatment of chylothorax in veterinary patients has yet to be proven.

Surgical intervention for the treatment of idiopathic chylothorax in dogs and cats is often undertaken, as medical management is rarely successful in resolving this disease. The prolonged loss of chyle into the thoracic cavity can lead to a metabolically compromised state for your pet. Also, the prognosis for clinical improvement decreases if inflammation of the lining of the lungs is present due to chronic chyle exposure. Should your pet need to undergo surgery for the treatment of chylothorax, you should inquire about referral to an ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon.

The most commonly performed surgical technique for resolving chylothorax is thoracic duct ligation (TDL). The purpose of this procedure is to promote new lymphatic connections to the venous system in the abdomen by preventing chyle flow into the TD. This will effectively prevent leakage of chyle from the TD into the thoracic cavity. Recently, TDL has been combined with removal of the lining of the heart (pericardectomy), which has resulted in higher success rates compared to TDL alone. Also, a tube will be placed in the chest that can be aspirated post-operatively. Some veterinary surgeons will also perform an abdominal surgery to allow for the injection of a contrast material into an intestinal lymphatic vessel or lymph node to allow for the delineation of TD anatomy and confirm TDL after surgery (lymphangiography, Figure 2).

Another technique that has shown promise in the surgical treatment of chylothorax is ablation of the cisterna chyli (CCA). The cisterna chyli is a reservoir of lymphatic fluid that resides in the abdomen. CCA destroys this reservoir and allows the body to create alternative pathways for the lymph fluid to enter the bloodstream, thereby relieving pressure on the thoracic duct.

Video-assisted thoracoscopy is a minimally invasive alternative to thoracic surgery and has been used to perform TDL, pericardectomy, and CCA in dogs. Recently, minimally invasive techniques for performing lymphangiography have also been described and can significantly reduce the time required to perform lymphangiography and alleviate the need for an abdominal surgery.

Surgery for chylothorax may be time consuming and your pet is at an increased anesthetic risk as they are likely metabolically compromised. Complications can include hemorrhage, infection, damage to the nerves that control the diaphragm, and persistent accumulation of fluid within the chest.

Your pet will likely recover in the intensive care unit (ICU) of the hospital where they will be administered medications to relieve pain and have the chest tube aspirated intermittently. Oxygen supplementation may also need to be provided in the immediate post-operative period. Your pet can be discharged after surgery once their chest tube production resolves or is reduced enough allowing for chest tube removal and intermittent thoracocentesis should their clinical signs return. In successful cases, the chylous effusion resolves several days to weeks after surgery.

Reported success rates for the alleviation of chylothorax in dogs and cats undergoing TDL is variable (40-60%). The combination of TDL and pericardectomy has improved success rates (80-100%) in dogs, however, in cats the prognosis remains variable, approximately 50%. Should surgical methods fail to resolve chylothorax, alternative surgical techniques can be discussed with your surgeon in an attempt to prevent the accumulation of chyle in the thorax.

Chylothorax is a poorly understood disease and it is important to realize that treatment (medical or surgical) may not be successful.