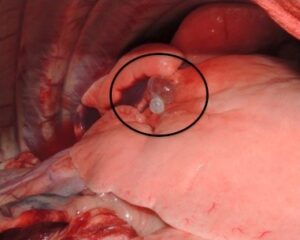

Spontaneous pneumothorax can be seen in both dogs and cats and occurs when air enters the chest cavity with no clinical history of trauma or iatrogenic penetration into the chest cavity. Normally, there is a physiologic negative pressure within the chest that is responsible for maintaining inflation of the lungs. When this is lost, air will accumulate within the chest cavity and subsequent collapse of the lungs occurs. Anatomically there are two primary routes of entry of air into the chest resulting in a spontaneous pneumothorax: the airways and the esophagus. The first occurs when there is compromise of lung or tracheal tissue resulting in inhaled air escaping into the chest cavity and accumulating around the lungs. Compromised lung tissue leading to a spontaneous pneumothorax is often caused by bullae or bleb formation at the edges of the lung lobes. These are small air filled sacs that can rupture within the chest cavity (Figure 1). Bullae and blebs are most commonly found in dogs with no concurrent lung disease and is the most common cause of spontaneous pneumothorax. Bullae and blebs are less common in cats with lung disease causing most of the cases of spontaneous pneumothorax.

The second route of entry into the chest is from esophageal perforation that results in both a pneumothorax and additional air accumulation in secondary anatomic locations (i.e. under the skin and around the structures of the heart). Secondary causes of spontaneous pneumothorax include:

Dogs

- Cancer

- Bacterial pneumonia

- Pulmonary abscess

- Fungal infection

- Heartworm disease

- Pulmonary thromboembolism

- Grass awn migration

Cats

- Lung Disease

- Inflammatory airway disease

- Heartworm infection

- Lung worm infection

- Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- Unknown

Spontaneous pneumothorax occurs primarily in deep chested, large breed dogs with no sex predilection. Siberian Husky dogs and other Northern breeds are overrepresented. There is no known common linkage in cats. Common clinical signs include:

Dogs

- Increased respiratory rate

- Coughing

- Anxiety

- Dusky blue mucous membranes (gums)

- Overinflated chest

- “Orthopneic” posture – this occurs in an attempt to open the airways and includes stretching of the neck and outward positioning of the elbows

Cats

- Respiratory distress such as increased respiratory rate and effort

- Cough

- Collapse

- Lethargic and anorexic

- Vomiting

- Hiding

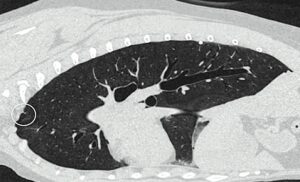

When presenting your pet to your primary care veterinarian they will most likely recommend chest X-rays to look for air within the chest cavity not contained within the lungs (Figure 2). This diagnostic test is very accurate for diagnosing the presence of a pneumothorax. However, it rarely confirms the underlying cause and additional advanced imaging such as a CAT scan often becomes necessary (Figure 3). An ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon will be able to determine the most appropriate imaging modality and discuss potential causes and treatments after reviewing the images.

Treatment options for your pet vary depending on the severity of the clinical signs. Initial stabilization is paramount as spontaneous pneumothorax can be life threatening due to the reduction of appropriate ventilation. Your primary care veterinarian may initially recommend a thoracocentesis. This is a procedure where a small needle is inserted into the chest cavity to remove the air around the lungs, allowing your pet to breath more comfortably. This temporary treatment does not address the underlying cause of the pneumothorax, but it allows the lungs to expand more normally potentially saving the life of your pet.

Generally, long-term treatment options can be separated into medical or surgical treatments. The underlying cause of a spontaneous pneumothorax dictates which treatment option will be most appropriate. Your primary care veterinarian and ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon will work with you and your pet to make the best decision.

Medical treatment includes:

- Oxygen supplementation

- Thoracostomy tube (chest tube)

Oxygen therapy is important because as the lungs collapse, secondary to losing negative intrathoracic pressure, the ability to deliver oxygen to the body also decreases. By providing supplemental oxygen, this helps the body deliver adequate oxygen to each organ system. Thoracostomy tubes are hollow tubes placed through the skin into the chest cavity (Figure 4). This allows either intermittent or continuous removal of air from the chest. This helps your pet’s lungs expand more normally sending appropriate levels of oxygen to the rest of the body. Most often, spontaneous pneumothorax cannot be managed medically long-term and surgical intervention is warranted to remove the primary cause of the air leaking into the chest.

Surgical treatment most often includes removal of the entire affected lung lobe(s) by entering the chest and performing a lung lobectomy (Figure 5). This can be accomplished using three different approaches to the chest cavity: minimally invasive thoracoscopy, median sternotomy (through the sternum), or a lateral thoracotomy (between the ribs). Each approach has its respective advantages depending on the underlying cause of the disease, location of the affected lung lobe, and availability of equipment. Your pet’s ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon will evaluate your pet’s specific case to make the best recommendation.

Long-term outcomes for dogs with spontaneous pneumothorax are excellent with surgical intervention and removal of the inciting cause of the air leakage. Some causes of the air leakage are not amenable to surgical resection and those pet’s prognoses vary depending on the severity and extent of the disease. Recurrence rates of spontaneous pneumothorax are approximately 3% with surgical treatment, and as high as 50% without surgical treatment. Mortality rates reflect the necessity of appropriate surgical management, as there is a 12% mortality rate with surgery and over 50% with medical management alone.

Outcome data for cats is more limited. The prognosis can still be good overall depending on the underlying cause and response to therapy. In a 2012 study 54% survived to hospital discharge with most being treated medically. For cat patients with small volume pneumothoraxes, conservative therapy may offer a good outcome though surgery may be needed in severe cases or when there is persistent pneumothorax present. A discussion with an ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon can help guide you in what’s best for your pet.