Urinary stones (urolithiasis) are a common condition responsible for lower urinary tract disease in dogs and cats. The formation of bladder stones (calculi) is associated with precipitation and crystal formation of various minerals. Several factors are responsible for the formation of urinary stones. The understanding of these processes is important for the treatment and prevention of urinary stones. In general, conditions that contribute to stone formation include:

- a high concentration of salts in urine

- retention of these salts and crystals for a certain period of time in the urinary tract

- an optimal pH that favors salt crystallization

- a scaffold for crystal formation

- a decrease in the body’s natural inhibitors of crystal formation.

The sequence of events that triggers stone formation is not fully understood. High dietary intake of minerals and protein in association with highly concentrated urine may contribute to increased saturation of salts in the urine. Disease conditions such as bacterial infections in the urinary tract can also increase urine salt concentration.

The signs that your pet may show depend on the location of the urinary stones. Most urinary stones are located in the urinary bladder or urethra and only a small percentage are lodged in the kidneys or ureters. Urinary stones can damage the lining of the urinary tract causing inflammation. This inflammatory reaction may predispose your pet to bacterial urinary tract infection (UTI).

Signs of bladder stones may include:

- blood in the urine

- straining to urinate

- urinating small amount frequently

- abdominal discomfort

- urinary accidents

Urinary stones may physically block the urine flow causing urinary obstruction that requires immediate emergency treatment.

Signs of urethral stones may include:

- dribbling urine

- straining or posturing to urinate with no urine production

If your pet is showing the above signs of a urinary obstruction, you should seek veterinary attention immediately.

Stones may also become lodged in the ureter (the portion of the urinary tract carrying urine from the kidney to the urinary bladder) causing an obstruction that results in serious kidney damage.

Signs of ureteral stones may include:

- abdominal discomfort

- decreased appetite

- lethargy

- vomiting

- blood in the urine

Your primary care veterinarian will likely recommend evaluation of your pet’s blood and urine. Urinary obstruction can cause heart rate and rhythm abnormalities seen on ECG. Identifying urinary tract infections associated with urinary stones requires culture not only of the urine but also of the bladder lining or the urolith (bladder stone).

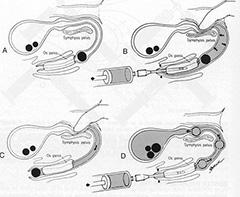

Several diagnostic imaging tests can be performed to assess the urinary tract. X-rays (radiography) and ultrasound are the most performed imaging techniques. Most, but not all, stones will show up on radiographs (Figure 1). Stones that do not show up well on plain radiographs may be diagnosed by introducing a contrast agent and/or gas into the urinary tract, usually through a urinary catheter.

Ultrasound examination can be very useful in evaluation of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder but has limited ability to evaluate the urethra. Another technique that has been used more recently is nuclear scintigraphy, which provides a non-invasive method for analysis of renal blood flow and function.

Types of Urinary Stones

The stone type is named after its mineral composition. The most common stones are struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate), calcium oxalate, urate, cystine, and silica.

Struvite Stones

The most common mineral type found in dogs is magnesium ammonium phosphate hexahydrate (struvite, Figure 2). This type of urinary stone accounts for 50% of all canine urinary stones. The prevalence in cats is around 30%. Miniature Schnauzer, Miniature Poodle, Bichon Frise, and Cocker Spaniel are the most affected breeds. Urinary tract infection is an important factor in the formation of struvite stones. The enzymatic action of some bacteria on urea increases the pH of the urine, which decreases the solubility of struvite crystals. Inflammation of the lining of the urinary bladder increases the amount of organic debris in the urine providing a surface for crystallization.

Calcium Oxalate Stones

In dogs, calcium oxalate stones (Figure 3) account for about 35% of all stones, while they account for 50-70% of feline stones. Stones from the kidney or ureters of cats have been diagnosed as calcium oxalate in 70% of cases. Breeds that are most affected in dogs include Miniature and Standard Schnauzer, Miniature Poodle, Bichon Frise, Lhasa Apso, Yorkshire Terrier, and Shih Tzu. Burmese, Persian, and Himalayan cats are the feline breeds most commonly affected.

The cascade of events leading to calcium oxalate stone formation is largely unknown, but there is some indication that normal increases in urinary calcium concentration after feeding could be involved in stone formation. Decreased urine concentration of natural body crystal formation inhibitors, and increased dietary intake of oxalate may also play a role in calcium oxalate stone formation.

Urate Stones

Urate stone (Figure 4) formation in dogs may result from two different mechanisms. One is related to the high excretion of ammonium biurate crystals in cases of portosystemic shunts. Dalmatian dogs, which have a defective hepatic membrane transport of uric acid, will also frequently form urate stones. These stones may be difficult to visualize with a radiograph but are observed easily with ultrasound.

Cystine Stones

Excessive elimination of cystine in the urine is an inherited disorder of kidney tubular transport that is thought to be the primary cause of cystine stones (Figure 5). High concentrations of cystine in an acidic environment (low pH) can lead to stone formation. Male Dachshunds between the ages of 3 and 6 years old are most commonly affected. Stones may be faintly visible on x-rays, but are most clearly visualized with ultrasound.

Silicate Stones

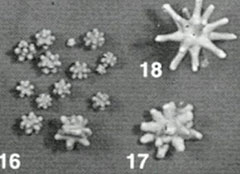

The mechanism of formation of silicate stones (Figure 6) is unknown; however, there may be a relationship between this type of stone and the dietary intake of silicates, silica acid, and magnesium silicate. The formation of these stones has been linked to the consumption of large amounts of corn gluten and soy bean hulls which are high in silicates. German Shepherds, Old English Sheepdogs, and Golden and Labrador Retrievers are the most affected breeds.

The exact aftercare will depend on the location of the stones and the procedure that your pet has undergone. In general, potential complications include infection, recurrence of stones, stricture formation (more so with surgery of the urethra or ureter), and blood in the urine. Your pet may need to wear an E-collar to prevent self-trauma to the surgery site. You should monitor your pet for the appropriate passage of urine after surgery, as well as a return to normal appetite and energy levels. It is common for pets to have a small amount of blood in the urine for the first week or two after urinary surgery.

Many of these stones have a high recurrence rate.

Prevention

Struvite stones: Your veterinarian will have specific recommendations for diets, as well as frequent monitoring of the urine. The treatment of any urinary tract infections is essential for the success of preventive measures.

Calcium oxalate stones: Your veterinarian will have specific recommendations for diets, as well as frequent monitoring of the urine.

Cystine stones: Your veterinarian will have specific recommendations for diets, as well as frequent monitoring of the urine. The pH of the urine should be kept above 7.5. Your veterinarian may recommend a dietary additive to raise the pH of the urine.

Urate stones: Your veterinarian will have specific recommendations for diets, as well as frequent monitoring of the urine. Dogs and cats with portosystemic shunts should have this condition addressed via either medical or surgical intervention. Dalmatians may benefit from a medication that modifies liver metabolism. Urate stones can be prevented in 80% of dogs and 95% of cats.

Silicate uroliths: Your veterinarian will have specific recommendations for diets, as well as frequent monitoring of the urine. Diets with excessive silicates should be avoided.