Nasopharyngeal polyps are benign, fleshy, inflammatory masses found in the nose, nasopharynx (above the soft palate), middle ear, and/or external ear canal. They occur mainly in cats and less frequently in dogs. In dogs, they usually extend into the ear canal rather than the back of the throat.

The exact cause of polyps is unknown. They usually occur in younger cats, and littermates can be affected. It is suspected that cats may develop them because of inflammation caused by infectious agents such as respiratory viruses. However, several studies have so far failed to identify an infectious agent. Also, although bacterial infections are commonly associated with polyps, antibiotic therapy alone does not resolve the polyp.

Most polyps originate from the lining of the middle ear (tympanic cavity). Polyps can grow up to 2 cm in diameter and usually develop on a stalk. As they grow, they can either burst through the eardrum into the external ear canal or extend through the Eustachian tube, which connects the middle ear to the back of the throat. In a small number of cases, polyps can grow in both directions. They usually only occur on one side; however, in cats, bilateral polyps have been reported in 13%-24% of cases.

Clinical signs are dependent on the location of the polyp. Nasopharyngeal polyps typically cause upper respiratory signs associated with breathing obstruction and secondary bacterial infections. Clinical signs may include:

- sneezing,

- noisy/labored breathing (Fig.1),

- difficulty eating/ swallowing,

- nasal discharge, and

- change in vocalisation,

Polyps affecting the middle ear or external ear canal typically present with middle and external ear infections. Clinical signs may include:

- head shaking,

- discharge from the ear canal,

- pawing or scratching at the ear,

- abnormal eye movements (nystagmus),

- head tilt,

- loss of balance (ataxia),

- change in appearance of the eye on the affected side (Horner’s Syndrome)

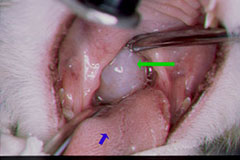

Nasopharyngeal polyps can be seen (Figures 2 and 3) or felt under the soft palate, the muscular layer of tissue that separates the back of the nose and mouth.

If the polyp is large enough, it may push the soft palate downward. Polyps may also be visualized by retroflexing a flexible endoscope over the soft palate. Otoscopic examination is used to identify polyps extending into the external ear canal. If the polyp is contained within the middle ear, the ear drum (tympanic membrane) may be discolored or distorted.

In cases in which a polyp cannot be easily identified, radiographs may be taken and evaluated for soft tissue changes associated with a polyp (Fig 4). More frequently advanced imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended as these techniques provide more information on the location of the polyp and the extent of the disease.

Presurgical biopsy of a nasopharyngeal polyp is not generally performed, especially if it is causing significant airway or swallowing obstruction. Evaluation of a removed polyp is recommended to confirm it is benign.

Polyps within the external ear canal and nasopharynx can be removed by gentle, steady traction (pulling) on the mass (Figures 5 and 6). General anesthesia is necessary. The stalk of the polyp should be removed to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Unfortunately, the base of the polyp can be difficult to remove by traction alone, and in many patients the mass will regrow. Therefore, removal of the base of the mass through a ventral bulla osteotomy (opening up the bony middle ear) is often performed to reduce the incidence of recurrence. Your veterinarian may refer your pet to an ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon for this procedure.

Most cats recover rapidly from the surgery and need no special care.

Post treatment complications are common after traction +/- ventral bulla osteotomy but are usually temporary. These include:

- Horners’s syndrome (see figure 8)

- Balance problems

- Head tilt

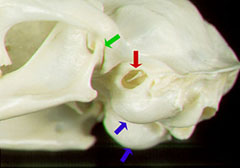

Several important structures are found along the outside of, or within, the bony structure (“bulla”) that forms the middle ear (Figures 7 and 8).

Within the bulla, some of the nerves to the eye cross along the inner wall. These nerves are often damaged when the polyp is pulled by traction or when a ventral bulla osteotomy is performed. About 80% of cats will develop Horner’s syndrome after this procedure because of damage to these nerves (Figure 8). In affected cats the third eyelid is elevated, the pupil is constricted and the upper eyelid droops. Horner’s syndrome is usually temporary and does not affect the cat’s vision or behavior.

Since the opening to the inner ear is also found in the bulla, post-operatively, some cats may develop balance problems (wobbliness), a head tilt, and rapid uncontrolled movements of their eyes (nystagmus). This condition is usually temporary, but can affect the cat’s well-being whilst it lasts. The lining of the bulla, which is the source of the polyp, must be gently removed to prevent polyp recurrence whilst minimizing damage to vital structures within the bulla.

Home care

Patients who have had a ventral bulla osteotomy are usually given pain medication. Antibiotic therapy after surgery may be recommended if concurrent infection is suspected.

Corticosteroid therapy has been used in some patients with inflammatory polyps treated with traction alone in an effort to reduce polyp recurrence.

An Elizabethan or comfy collar may be recommended to protect the incision from scratching.

Wet food may be recommended whilst wound healing occurs. If your pet is not eating after surgery you contact your surgeon or primary care veterinarian immediately for advice.

Prognosis

The prognosis for recovery is excellent even in cats that develop Horner’s syndrome or balance problems after surgery, since these signs usually resolve within a month. Traction combined with ventral bulla osteotomy has a low recurrence rate (<2-10%) compared to traction alone (30-50%).