A portosystemic shunt (PSS) is an abnormal connection between the portal vascular system and systemic circulation. Blood from the abdominal organs, which should be drained by the portal vein into the liver, is instead shunted to the systemic circulation by the PSS or shunting vessel. This means that a portion of the toxins, proteins, and nutrients absorbed by the intestines bypass the liver, resulting in decreased hepatic blood flow and impairment of normal hepatic metabolic functions, and are shunted directly into the systemic circulation.

There are two categories of congenital shunts, extrahepatic (outside the liver) and intrahepatic (inside the liver). While most portosystemic shunts are congenital (the dog or cat is born with the shunt), under certain circumstances, portostystemic shunts may be acquired secondary to another problem with the liver (acquired shunts). In a normal pet, the blood that exits the intestines, spleen, and pancreas enters the portal vein, which then takes blood to be filtered by the liver. The liver metabolizes and detoxifies this blood. If a shunt is present, the liver is deprived of factors that enhance liver development (hepatotrophic factors), which results in failure of the liver to reach normal size (hepatic atrophy). A common result of hepatic atrophy is hepatic insufficiency, which then combined with the circulating toxins proteins and nutrients frequently results in hepatic encephalopathy (a clinical syndrome of altered central nervous system function due to failure of normal liver function).

The genetic basis of PSS in dogs is unknown, but it is considered congenital with breeds affected including:

- Miniature Schnauzers

- Yorkshire Terriers

- Irish Wolfhounds

- Cairn Terriers

- Maltese

- Australian Cattle Dogs

- Golden Retrievers

- Old English Sheepdogs

- Labrador Retrievers

Single extrahepatic shunts are typically congenital and more often affect small and toy breeds whereas single intrahepatic shunts more often affect large breeds. Cats nearly always have extrahepatic shunts, and the left gastric is the most common.

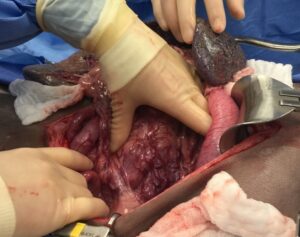

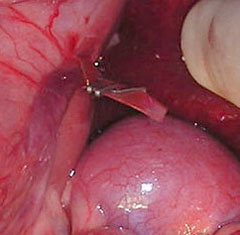

Acquired PSS (figure 1) are almost always multiple vessels, which develop in response to hepatic hypertension. They can occur in any breed or age of animal and are a compensatory mechanism to prevent or delay liver failure. As such, they cannot be ligated without causing severe symptoms, and medical management is the only option for treatment.

Animals with congenital portosystemic shunts may present for:

- small body stature

- anesthetic intolerance – prolonged recovery following an anesthetic event

- behavioral abnormalities

The behavioral abnormalities are often episodic and may be more noticeable after eating. These neurological signs are due to the hepatic encephalopathy syndrome since the liver is no longer able to detoxify the blood from the gastrointestinal tract. Signs of abnormal neurologic function include:

- ataxia (swaying as if intoxicated)

- seizures

- blindness

- head pressing

Other signs may include:

- anorexia (loss of appetite)

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- constipation

- ptyalism (hypersalivation) – most frequently seen in cats

- polyuria/polydipsia (excessive urination/drinking)

- stranguria (difficulty urinating)

- hematuria (blood in the urine)

If your primary care veterinarian suspects that your pet has a portosystemic shunt, a full diagnostic work-up is advised. Some of these diagnostics may be completed by your primary care veterinarian, but you may also be referred to an ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon or veterinary specialty center for additional diagnostics. A full work-up may include:

- blood work

- urinalysis

- liver function tests (bile acids and ammonia). Bile acids are measured after an overnight fast (“preprandial” or fasting) and then 2 hours after eating (“postprandial”). In dogs with PSS, one or both sets of bile acids are increased. Bile acids can increase with any liver disease, so high bile acids are not specific to congenital portosystemic shunts.

- abdominal radiographs

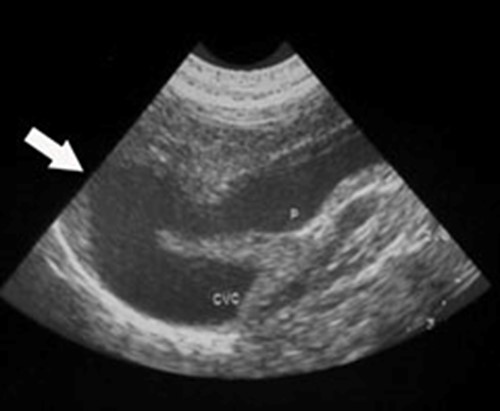

- abdominal ultrasound (Figure 2)

- nuclear scintigraphy (a non-invasive technique involving colonic administration of a radioisotope)

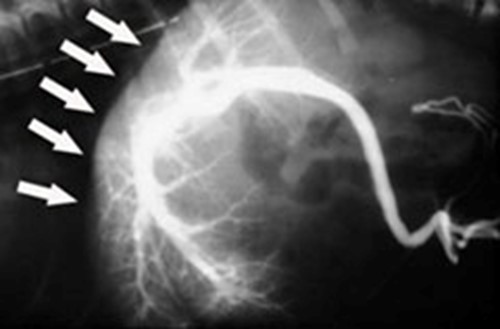

- portography (an x-ray dye study that specifically highlights the portal system, (Figures 3 and 4))

- CT scan with intravenous contrast

Medical management

Before surgery can be performed, your pet may need to be stabilized medically. The goal of medical management is to improve your pet’s health to a point where the risk of anesthesia and surgery is low. Medical management consists of a low protein diet and oral administration of antibiotics and lactulose. The goals are to decrease the bacterial population in the intestines and to minimize the production of toxins. Lactulose is an osmotic laxative, which both decreases the bacterial load in the colon and changes the large intestinal pH to reduce the ammonia produced and subsequently absorbed. Antibiotics also help to eliminate bacteria that promote the formation of toxins. The diet should provide high-quality protein but may need to be moderately restricted in amount of protein, depending on the clinical signs for each individual animal. If seizures are a part of clinical signs, anti-seizure medication may also be used. Keppra (levetiracetam), an anti-seizure medicine, has been possibly shown to reduce the occurrence of post-operative seizures, which is a rare but potential devastating complication.

Surgical management

The treatment of choice for a single PSS is surgical attenuation (narrowing) with eventual closure of the abnormal shunt vessel or full ligation if deemed appropriate by your surgeon. Complete ligation should never be done instantaneously in all patients with portosystemic shunts, which could lead to life-threatening portal hypertension, seizures, and death in some patients with under-developed portal vasculature. Attenuation, or gradual closure, is a delayed full ligation with an ameroid ring constrictor, cellophane band, hydraulic occluder placement, or intravascular techniques. This surgery is technically challenging, and your primary care veterinarian may refer you and your pet to an ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon.

If a shunt cannot be identified at surgery, an intra-operative portogram is performed (figures 3 and 4). When the shunt is identified, pressure in the portal vein may be measured (figure 5) to determine if complete ligation is possible. Excessively high portal system pressure, called portal hypertension, can result in death. Acute portal hypertension results in abdominal distension, pain, bloody diarrhea, ileus (stasis of bowel with gas build-up) and endotoxic shock (shock due to bacterial toxins).

Partial ligation of the shunt may be done by partially enclosing the vessel with a suture ligature until pressure rise is at its acceptable limit. About half of patients using this method will go on to scar close their shunts; but about half will maintain some shunting of blood and need a second surgery months later, when the liver has adapted to its new circulation and can withstand full ligation. This method is rarely used anymore to address single extrahepatic shunts, although in intra-hepatic shunts, partial ligation or trans-venous coils can be used to address the shunting vessel. Due to the availability of ameroid constrictors, intravenous coils and cellophane bands, partial ligation is rarely used in single extrahepatic shunts.

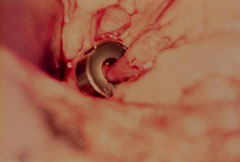

The ameroid constrictor (Figure 6, 7) is made of casein in a stainless steel, “C”-shaped ring. It is placed around the shunt, and the ring is closed with a small key.

Over the next few weeks, the casein swells and gradually occludes the shunt (Figure 7). This is considered a method of gradual occlusion.

The vessel may also be occluded using a special cellophane band (Figure 8). The band will incite an inflammatory response, and the vessel will slowly close down over a period of months.

Trans-venous coiling is usually used for larger, intra-hepatic shunting vessels. This is a minimally-invasive procedure in which coils are placed in the portosystemic shunt to allow the shunt to close down progressively over time. The coils are held in place by the use of a metal or metal-alloy stent. The entire procedure is performed through a small puncture in a blood vessel in the neck region. The goal of the procedure is to help the liver be able to perform normal functions more effectively as more blood travels through the liver.

At the time of shunt attenuation, your veterinarian may also recommend cystotomy if bladder stones are present.

Routine postoperative management includes intravenous fluids and pain medications. Lactulose and diet modification are continued, as it takes time for the liver cells to regenerate, adjust to the new circulation, and gradually accept more blood flow. These medications may be tapered depending on follow-up bile acid test results. Because serum bile acids values may or may not improve, some dogs may need long term treatment, whereas others may only need some dietary restrictions or no medical restrictions. After ligation, the liver should regenerate. Failure of the procedure can occur for any of the following reasons:

- failure of shunt to close or attenuate

- recanalization of the shunt (the shunt reopens)

- the presence of a second, unrecognized shunt (extremely unlikely)

- the development of multiple acquired PSS secondary to portal hypertension or fibrosis (scarring) of the liver

Complications after surgery include portal hypertension, which can lead to loss of proper blood circulation to abdominal organs and death. Animals may show signs of:

- ascites (fluid distension in the abdomen)

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- depression

- respiratory distress

Use of gradual occlusion devices has substantially reduced the chance of death by portal hypertension.

One of the most problematic but rare complications is development of seizures that are refractory to treatment. This occurs most frequently in toy breed dogs, in the first 1-2 days after surgery. The cause of these seizures is unknown. Seizures may be managed with anti-seizure medication (Keppra –as mentioned previously). In a recent study Keppra (Levetiracetam) was administered to 33% (42/126) of dogs. No dog treated with LEV experienced postoperative seizures, whereas 5% (4/84) of dogs not treated with LEV experienced postoperative seizures. In severe cases, intravenous administration of anti-seizure or anesthetic agents may be required to control seizures. Development of seizures that are poorly controlled by medication carries a very poor prognosis.

The prognosis is excellent if the animal survives the immediate postoperative period and full ligation of the shunt is achieved. With partial ligation, the prognosis is not as good. In many cases, full ligation is possible in animals that were partially ligated 4-6 months previously, so follow-up bile acids tests and portal scintigraphy should be done to monitor for shunt function.

** Both medical and surgical treatment can be used to achieve long-term survival of dogs with CPSS, although results of statistical analysis support the widely held belief that surgery is preferable to medical treatment. Although surgical intervention was associated with a better chance of long-term survival, medical management provides an acceptable first-line option. Dogs with CPSS that do not achieve acceptable resolution with medical treatment can subsequently be treated surgically.