In healthy cats and dogs, a large force (trauma) is required to fracture the mandible (lower jaw). A fracture is a break in the bone and can range in severity from a greenstick (incomplete crack) fracture to severe comminution (many pieces). Vehicular trauma is the most common cause of mandibular fractures. Due to the intensity of trauma associated with mandibular (lower jaw), maxillary (upper jaw), or skull fractures, the injuries may not be limited to the facial region and pets often require treatment for other injuries before the fracture is definitively addressed. Your primary care veterinarian may recommend radiographs of other parts of the body before focusing on the mandible. Thoracic (chest) injuries often occur concomitantly and may manifest as pulmonary contusions (bruising of the lungs), pneumothorax (punctured lung), diaphragmatic hernia, and traumatic myocarditis (bruising of the heart causing arrhythmias). It is very important to assess the whole body first as these other injuries could be life threatening.

Occasionally, there is no history of trauma. In these cases a pathologic fracture (fracture caused by disease) must be considered. Disease such as severe tooth/jaw bone decay, and cancer, can weaken the bone and predispose it to fracture. Pathologic fractures tend to affect older animals more commonly than younger animals.

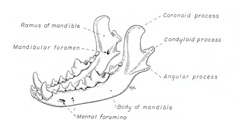

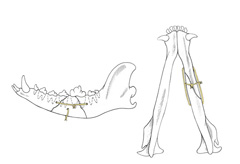

The mandible and maxilla have unique features compared to the rest of the skeleton that complicate fracture management. The mandible is comprised of two bones joined on midline by a symphysis (non-moveable joint) (Figure 1). The tooth roots, nerves, blood vessels, and salivary ducts are located within and adjacent to the mandible. These structures are frequently traumatized along with a mandibular fracture.

Symptoms of mandibular fractures include:

- reluctance to eat

- bleeding from the mouth

- malalignment of the jaw

- wounds around the mouth, pain and swelling in the region, a persistently open mouth

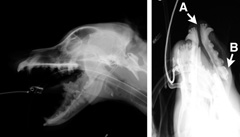

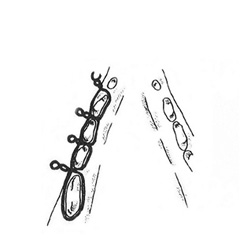

- excessive salivation that may be blood-tinged (Figure 2)

Due to the of the discomfort associated with this injury your veterinarian may recommend sedation or anesthesia for your pet prior to palpating the injured area and performing further testing. Due to the minimal amount of soft tissue that covers the mandible, it is common for these fractures to be open. An open fracture is a fracture that has resulted in loss of integrity of the protective layer of soft tissue around the bone, exposing the disrupted bone edges to the external environment (Figure 2).

After your veterinarian determines that your pet is stable enough to focus on tests for and treatment of the mandibular injury, X-rays of the mandible will be recommended to confirm the presence of a fracture and to guide treatment recommendations (Figure 3). Due to the complex anatomy of the mandible, teeth, and skull, radiographs are usually performed under heavy sedation or general anesthesia. This will decrease stress on your pet and allow for optimal positioning to interpret the complicated images. In some cases, a CT (computed tomography or “CAT”) scan may be recommended to gain more information regarding the complex anatomy to allow for an optimal surgical plan.

External immobilization may be placed. Reduction entails manipulating the bone fragments into alignment to minimize discomfort. External immobilization is usually some form of a muzzle, either custom made from medical tape or a commercial muzzle. In some cases, external immobilization is all that is required for treatment.

Surgical treatment of mandibular fractures is recommended when the fracture is unstable, multiple fractures/ pieces are present, and/or both sides of the mandible are affected. Surgery is performed to restore proper occlusion (normal scissor-like interaction of the teeth) of the teeth, improve comfort and cosmetic appearance, and provide early return to function.

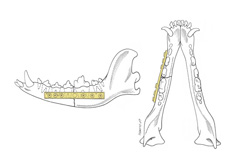

Multiple methods of treating mandibular fractures are available, and your surgeon (Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Surgeons) or veterinary dentist (Diplomate of the American Veterinary Dental College) will determine which method is most appropriate for your pet. Internal reduction and stabilization with bone plates and screws is a widely utilized surgical treatment (Figure 4). This entails making an incision in the region of the fracture, reducing (re-aligning) the fracture segments and then stabilizing the fragments with a surgical bone plate and screws. Advantages include early return to function and the minimal postoperative care required compared to other techniques.

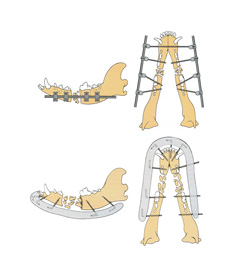

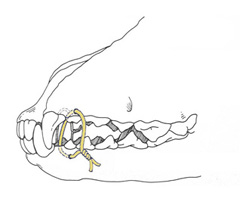

Another surgical treatment may involve the use of external skeletal fixation (ESF) (Figure 5). ESF involves placing pins through the skin into the bone fragments and then connecting these pins to a connecting rod that provides stability so that proper healing can occur. The majority of the ESF construct is on the outside of the animal and some postoperative care is required. Advantages of ESF are that the construct may be placed in a less invasive fashion and once the fracture is healed, the implants are completely removed. Other surgical treatments include use of intraoral splints, interosseous or interfragmentary wiring, interdental wiring, or interarcade wiring (Figure 6a, 6b, 6c). A veterinary dentist may present additional treatment options for mandibular fractures. In some cases, placement of a feeding tube may be recommended for nutritional support while the fracture is healing.

Potential complications include:

- tooth malocclusion

- infection

- delayed/incomplete bone healing

- failure of bone healing

Malocclusion of teeth is the most commonly reported complication and can lead to jaw joint dysfunction, excessive wear of teeth, injury to the surrounding oral tissues, periodontal disease, pain, and difficulty eating. Once malocclusion occurs, it is challenging to treat.

Pain medications are routinely prescribed following treatment of a mandibular fracture. Many veterinary surgeons will also recommend a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) that has been formulated specifically for dogs or cats. In most cases antibiotics will be prescribed due to the high incidence of open mandibular fractures.

Pets should be discouraged from playing with toys or other animals, chewing on bones, or engaging in any activity that may place stress on the fracture site and compromise healing of the fracture. If external immobilization is utilized, it may be recommended to inspect the site of the muzzle for irritation or accumulation of food debris, as dermatitis is common. In pets treated by immobilization or with fixation that limits opening or closing of the mouth, care must be taken to avoid excessive activity and to restrict outdoor activity to the cooler parts of the day. Dogs regulate body temperature by panting, and if panting is impeded by the muzzle or a closed mouth surgery technique, body temperature can rise rapidly.

Diet change during their recovery. If your pet eats a dry kibble diet, switching to a soft diet or soaking the dry diet in warm water to soften the kibble prior to serving may be recommended. This will minimize stress on the healing bones and minimize trauma to the healing soft tissues within the mouth. In cases that have had feeding tubes placed, instructions on how to care for the tube and how to feed through the tube will be provided.

Food debris may accumulate if intraoral splints, interdental wires, or interarcade wires are utilized. You may be instructed to gently flush the mouth on a regular basis to keep the site free of debris. If external skeletal fixators are used to stabilize the fracture, the apparatus may need to be cleaned regularly and in some cases the fixators are bandaged and may require regular bandage changes.

Prognosis is generally very good if complications are avoided. As previously mentioned, malocclusion can result in additional procedures (e.g., tooth reconstruction, extraction, etc.) being necessary.