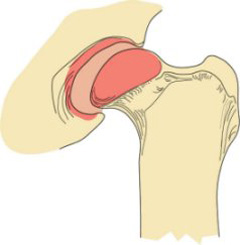

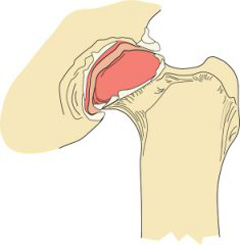

Canine Hip Dysplasia (CHD) is a condition that begins in dogs as they grow and results in instability or a loose fit (laxity) of the hip joint (Figure 1). The hip joint laxity is responsible for potential clinical signs (symptoms) of hip pain and limb dysfunction and progressive joint changes. The hip joint is a ball and socket joint and continual abnormal movement of the femoral head (ball) deforms the acetabulum (socket). The long-term response to this joint laxity is the progressive loss of cartilage, the development of scar tissue around the joint, and the formation of osteophytes (bone spurs) around the ball and socket (Figure 2).

The cause of CHD is multifactorial; however, hereditary (genetics) is the biggest single risk factor. Rapid weight gain and growth through excessive nutritional intake can complicate the development of CHD. Hip dysplasia occurs most commonly in large breed dogs.

The symptoms of CHD are lameness (limping), reluctance to rise or jump, shifting of weight to the forelimbs, loss of muscle mass on the rear limbs, and hip pain. Generally, divide dogs with CHD into two groups showing symptoms of CHD:

Group 1: Younger dogs without arthritis, but with significant hip laxity

Group 2: More mature dogs that have developed hip arthritis due to CHD

Dogs may show symptoms at any stage of disease’s development, although many dogs with CHD do not have any obvious symptoms.

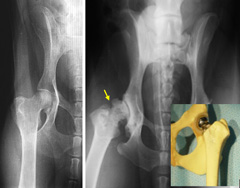

CHD is diagnosed by a combination of two methods. Specially positioned hip x-rays and special palpation methods that determine abnormal hip joint laxity, both require light sedation. The most accurate x-ray method at an early age is the PennHIP distraction method. This is a quantitative method that measures the actual amount of hip laxity. It accurately predicts whether a puppy will develop hip dysplasia and what surgical options would be best suited to prevent crippling arthritis (Figure 3). Special training and equipment are necessary to perform this test. PennHIP provides an independent written confirmation of CHD for the pet owner and examining veterinarian. Some primary care veterinarians and many ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeons have taken the training course and have the equipment to perform this test.

The palpation method is called the Ortolani Sign. It has been used in newborn children since 1937 and continues to be the “gold standard” for the early diagnosis of hip dysplasia in newborns around the world. It has been used in young puppies since the 1985 using light sedation. It is not quantitative, but if present confirms that the puppy will usually have hip arthritis by one year of age. Many primary care veterinarians can perform this exam during the early age, 10–16 weeks, vaccination exams. If the Ortolani Sign is not present, there is a false negative possibility that can be resolved by the quantitative PennHIP method.

Unfortunately, the often-used x-ray exam by the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals that most breeders use, is not accurate and predictive of CHD at very young ages. Their recommendation is a preliminary exam at 1 year and the final exam at 2 years of age. This is too late in the progression of CHD because the dogs with crippling arthritis have missed two surgical options (JPS and DPO/TPO, see Treatment) that can significantly reduce the effects of hip dysplasia by 1 year of age.

Early recognition of joint laxity is the key to preventing cartilage damage from progressive joint laxity.

Treatment Option 1:

Puppies as early as 10 weeks old can be diagnosed with abnormal joint laxity accurately (see Diagnostics) and treated surgically by the procedure, Juvenile Pubic Symphysiodesis (JPS). Between 10 and 18 weeks old, when a puppy is given their shots, they should be examined by the primary care veterinarian or an ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon to determine the absence or presence of pathological joint laxity which could result in CHD.

A recent study that reviewed many peer reviewed published scientific studies i.e. evidence based medicine stated, “JPS surgery is a method of consistently providing normal pain free hip function”. JPS is a minimally invasive surgery that closes a growth plate at the bottom of the pelvis. This results in selective growth of the pelvis and the hip cup (acetabulum) increasingly covering the ball (femoral head) as the puppy grows during the following 4–6 months. Patients may be able to go home the same day after this procedure.

During those 4–6 growing months, following JPS surgery, leash walks are acceptable but strenuous off leash exercise is discouraged until follow up exams at 10 months of age confirm the dog will have pain free hip function.

Weight management and rapid growth should be managed with measured amounts of low protein dry food diets (20–21%) for rapidly growing large breed puppies from an early age and following JPS surgery until 12 months of age.

JPS is a technique for stopping the growth of the pubis (part of the pelvis) to alter the growth/shape of the pelvis, while increasing the ball’s degree of coverage by the socket to diminish hip laxity. It is a relatively minor surgical procedure and puppies less than 18 weeks of age must have it performed. However, since most puppies of this age do not show symptoms of CHD, early diagnosis by way of examination and special x-ray techniques are critical.

Treatment Option 2:

Double or Triple Pelvic Osteotomy (DPO/TPO) is another option for immature dogs (ideally less than 8–10 months old) with CHD but no visible radiographic arthritic changes. These surgical procedures involve cutting the pelvic bone in two (DPO) to three places (TPO) and rotating the segments to improve coverage of the ball by the socket and decrease hip laxity (Figure 4). TPO has been used successfully in dogs and children for decades. Recent advancements in implant (locking plates and screws) technology now allow similar results with only two cuts made in the bone (DPO), thus a less invasive procedure.

The best time to recognize pathologic hip laxity is when the young dog is neutered (spayed or castrated) between 6–8 months old. This can often be done by the primary care veterinarian who does the sterilization procedure. An x-ray must be taken and the hips can be palpated for joint laxity (see methods under Diagnostics) Immature dogs with lameness and early evidence of hip arthritis are not ideal candidates for DPO/TPO, nor are dogs with very severe hip laxity, as some puppies have no functional hip joint by 6 months of age.

Treatment Option 3:

Total Hip Replacement (THR), the third surgical option, can be used in young dogs who cannot be successfully treated with JPS or DPO/TPO surgeries. They must be managed medically until they are mature enough for THR, at least a year old. THR, based on evidence based medicine via multiple peer reviewed publications is the second surgical method that provides the most normal pain free function in dogs with CHD.

This surgical procedure eliminates hip pain by reproducing the mechanics of a normal hip joint with a more natural range of motion and limb function. As with humans, canine THR involves replacement of both the ball and socket with metal and polyethylene (plastic) implants (Figure 6). These components are fixated in place with bone cement, metal pegs, or “press fit” (bone ingrowth) methods.

Treatment Option 4:

The last surgical option to alleviate the pain secondary to severe hip laxity/dysplasia is femoral head ostectomy (FHO) surgery. This surgical procedure can be done at any age and can provide enough comfort in a dog weighing less than 60–70 lbs to avoid the daily use of anti-inflammatory pain medication, thus avoiding costs and side effects that limit or negate its use.

Young dogs that do not meet the criteria for DPO/TPO or JPS procedures, or dogs who do not respond satisfactorily to medical treatment alone may benefit from FHO. This technique involves removing the femoral portion of the hip joint (i.e., the ball) to reduce the pain produced by abnormal hip joint contact that wears away the joint cartilage, and the stretching of the soft tissues around the joint due to laxity (Figure 5).

Following an FHO, a “false joint” develops with the muscles around the hip now transferring the forces from the leg to the pelvis during limb movement. The goal of an FHO is to relieve the pain associated with CHD, not to maintain/recreate normal hip function. Two weeks following FHO surgery the puppy/adult dog is encouraged to exercise, often receiving anti-inflammatory drugs daily during the initial 1–2 months post-op. Then these drugs may only be necessary intermittently.

FHO dogs must remain slim throughout their lives and follow a limited exercise program i.e. leash walks and confinement to the yard and house. They cannot be athletic dogs who hunt, do agility, high level obedience, run with their owners, etc. If those activities are what the owner wishes to do with their dog, then a THR would be necessary.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT:

This treatment option is dependent on many factors. Age, weight, degree of hip laxity, lifestyle of the owner and their tolerance for the cost incurred for medication and in some cases physical therapy.

AGE: Often used in middle aged to older dogs who have gained weight and live a relative sedentary life style.

WEIGHT: All dogs with CHD should be kept very slim from the outset, from very young to old age. It is the most effective least expensive long term method of keeping them as comfortable as possible.

DEGREE OF HIP LAXITY: This can vary greatly depending on the degree of hip laxity. The severely affected puppy with no functional hip joints at 6 months of age is destined for a life of daily pain with minimal exercise. The other end of that wide spectrum is the dog with hip laxity that is present but does not manifest itself until middle age. In this case, the cartilage damage progresses more slowly because of less severe hip laxity.

LIFE STYLE: Highly active owners or owners who introduce another young active dog/child to their home find they have an older dog with CHD. CHD dogs cannot be highly active/athletic without surgery. There are no medical management programs that will allow that lifestyle comfortably. A more sedentary, low impact lifestyle is a more realistic outcome with medical management.

WHAT DOES MEDICAL MANAGEMENT ENTAIL?

1) Maintenance of minimal body weight.

2) Limited exercise routine i.e. leash walks of a length the dog tolerates comfortably.

3) Daily or intermittent (a better option if it can be done effectively) use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These drugs can be very effective in relieving pain. However, NSAIDs can have significant side effects that if used daily must be monitored with blood tests to avoid kidney and liver damage. The monitoring interval depends on the age of the dog and the dosage level of the drug. Ideally the lowest daily dose that provides obvious comfort should be used for long term therapy. If the maximum daily dose is required, the risk of side effects is greater and the cost of the drug and monitoring can exceed the cost of surgical intervention if the dog is young or middle aged.

4) Cartilage protective supplements are often recommended, however there is no evidence in peer reviewed literature that they provide any help in cartilage repair or protection against wear/damage.

5) Animal derived/fish oil Omega-3 fatty acids as anti-inflammatory for joints

6) Physical therapy can be helpful in dogs who lead a very sedentary life style because the owners work long hours. The dog, like ourselves, become stiff if they do not move around frequently. Joint movement and muscle strength help keep them comfortable and more mobile. Physical therapy is also used for dogs undergoing surgery for CHD. This helps strengthen the muscles and increases the speed of recovery.

Risk of complications after JPS are very low; almost all are minor in nature. Success rates for JPS eliminating hip laxity are high and aftercare is very brief, usually just entailing basic incision care and short-term activity restriction.

Reported complications after DPO and TPO include screw loosening, change in limb range of motion, and pelvic canal narrowing. However, the incidence of complications is low and reports of long-term function are expected to be good to excellent.

THR results in an excellent chance of markedly improved limb function. Potential complications after THR include infection, hip dislocation, “loosening” of the implants over time, nerve injury, and femur fracture.

Following both DPO/TPO and THR, the dog’s activity should be restricted to leash exercise outdoors and confinement to a small area indoors until the procedures are deemed healed (via examination and X-rays), generally six and eight weeks respectively. Most pets are weight bearing soon after surgery and require supervision to prevent overuse of the leg during the healing period. If necessary, use a sling for initial assistance with walking. The dog should avoid stairs, slippery surfaces and interactions with other dogs. To get back to normal, slowly increase activity after the initial period of restriction.

Results after FHO vary and are highly dependent upon patient size and proper postoperative physical rehabilitation. While many dogs will have varying degrees of lameness, function should improve when compared with preoperative status. After FHO, pets are encouraged to use the limb as soon as possible in a controlled manner. Aggressive physical rehabilitation and controlled exercise to increase hip range of motion are essential for an optimal outcome. It may take up to six weeks or longer after surgery for some dogs to show improvement.