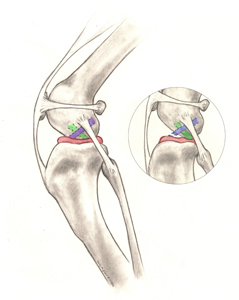

El ligamento cruzado craneal (LCCr, véase la Figura 1.) es uno de los estabilizadores más importantes dentro de la articulación de la rodilla (babilla) canina, la articulación media de la pata trasera. En los seres humanos, el LCCr se denomina ligamento cruzado anterior (LCA).

El menisco (Figura 1) es una estructura «cartilaginosa» situada entre el fémur (muslo) y la tibia (espinilla). Cumple muchas funciones importantes en la articulación, como la absorción de impactos, la detección de la posición y el soporte de carga, y puede dañarse cuando se rompe el LCCr.

La rotura del LCCr es una de las causas más frecuentes de cojera, dolor y posterior artritis de rodilla en las extremidades posteriores. Dado que la aparición de este problema en los perros es mucho más compleja que en los humanos, y que experimentan distintos grados de rotura (parcial o completa), la afección canina se denomina «enfermedad del ligamento cruzado craneal» (CrCLD, por sus siglas en inglés). Aunque los signos clínicos (síntomas) asociados a la CrCLD varían, la enfermedad provoca invariablemente disfunción y dolor en las extremidades posteriores.

En la mayoría de los casos, la CrCLD está causada por una combinación de muchos factores, como el envejecimiento del ligamento (degeneración), la obesidad, la mala condición física, la genética, la conformación (forma y configuración del esqueleto) y la raza. En el caso de la CrCLD, la rotura del ligamento es el resultado de una degeneración sutil y lenta que se ha ido produciendo a lo largo de unos meses o incluso años, y no el resultado de un traumatismo agudo (repentino) en un ligamento por lo demás sano (lo cual es muy poco frecuente). Esta diferencia entre personas y perros explica dos características importantes de la CrCLD canina:

- El 40-60 % de los perros que tienen CrCLD en una rodilla desarrollarán, en algún momento futuro, un problema similar en la otra rodilla.

- El desgarro parcial del LCCr es frecuente en los perros y casi siempre evoluciona a un desgarro total con el tiempo.

La enfermedad del ligamento cruzado craneal puede afectar a los perros de todos los tamaños, razas y edades, pero rara vez a los gatos. Se sabe que algunas razas de perro tienen una mayor incidencia de CrCLD (Rottweiler, Terranova, Staffordshire Terrier, Mastín, Akita, San Bernardo, Chesapeake Bay Retriever y Labrador Retriever), mientras que otras se ven afectadas con menos frecuencia (Galgo, Teckel, Basset Hound y Antiguo Pastor Inglés). Se ha demostrado un modo de herencia genética para los Terranova y los Labrador Retrievers.

Una mala condición física y un peso corporal excesivo son factores de riesgo para la aparición de la CrCLD. En ambos factores pueden influir los dueños de las mascotas. Se aconseja un acondicionamiento físico constante con actividad regular y una estrecha vigilancia de la ingesta de alimentos para mantener una masa corporal magra.

Los perros con CrCLD pueden presentar cualquier combinación de los siguientes signos (síntomas):

- dificultad para levantarse

- dificultad para sentarse («prueba de sedestación positiva»)

- problemas para subir al coche

- disminución del nivel de actividad o falta de ganas de jugar

- cojera de intensidad variable, que a veces solo se observa tras largos períodos de reposo

- atrofia muscular (disminución de la masa muscular en la pierna afectada)

- disminución de la amplitud de movimiento de la articulación de la rodilla

- un chasquido (que puede indicar una rotura de menisco)

- hinchazón dura en el interior de la tibia (fibrosis o tejido cicatricial)

- dolor

- rigidez

El dolor y el malestar se expresan de forma diferente en las personas que en los perros, por lo que, aunque los perros no gimoteen, griten o levanten constantemente la extremidad afectada, la persistencia de su cojera es dolor.

El desgarramiento completo del LCC puede ser diagnosticado con facilidad por el veterinario combinando la observación de la manera de andar, los hallazgos del examen físico y las radiografías. Sin embargo, el diagnóstico del desgarramiento parcial del LCC puede resultar más desafiante.

Las radiografías permiten al veterinario:

- confirmar la presencia de un derrame articular (acumulación de líquido en la articulación, que indica una anomalía)

- evaluar la presencia/grado de la artritis

- tomar medidas para la planificación quirúrgica

- descartar otras enfermedades simultáneas

Algunas de las técnicas específicas de palpación que usan los veterinarios para evaluar el LCC incluyen la «prueba del cajón craneal» y la «prueba de compresión tibial». Estas pruebas pueden confirmar un movimiento anómalo de la rodilla compatible con rotura del LCC.

El veterinario puede diagnosticar fácilmente los desgarros completos del LCCr mediante una combinación de observaciones de la marcha, resultados de la exploración física y radiografías. Por el contrario, los desgarros parciales del LCCr pueden ser más difíciles de diagnosticar y pueden requerir una inspección visual mediante artrotomía, miniartrotomía o artroscopia para confirmarlos.

Con las radiografías su veterinario puede:

- confirmar la presencia de una opacidad de los tejidos blandos compatible con un derrame articular (acumulación de líquido, en su mayor parte de naturaleza inflamatoria, en la articulación de la babilla, que indica la presencia de una anomalía)

- evaluar la presencia o el grado de artritis

- tomar medidas para la planificación quirúrgica

- descartar enfermedades simultáneas

Entre las técnicas de palpación específicas que utilizan los veterinarios para evaluar el LCCr se incluyen la «prueba del cajón craneal» y la «prueba de compresión tibial». Con estas pruebas se puede confirmar un movimiento anormal dentro de la rodilla compatible con la rotura del LCCr.

Antes de la intervención quirúrgica o de la administración de antiinflamatorios para aliviar el dolor, es probable que su veterinario también realice análisis de sangre o compruebe si se los han realizado recientemente a su mascota. Conocer el estado general de salud de su mascota es importante antes de decidirse por una cirugía ortopédica o administrar determinados medicamentos.

Existen muchas opciones de tratamiento para la CrCLD. La primera decisión importante es entre el tratamiento quirúrgico y el tratamiento no quirúrgico (también denominado conservador o médico). La mejor opción para su mascota depende de muchos factores, como su nivel de actividad, tamaño, edad, conformación ósea y grado de inestabilidad de la rodilla.

El tratamiento quirúrgico suele ser el mejor tratamiento para la CrCLD, ya que es la única forma de controlar de forma permanente la inestabilidad presente en la articulación de la rodilla. La cirugía aborda uno de los principales problemas asociados a la CrCLD: la inestabilidad de la rodilla y el dolor que provoca como consecuencia de la pérdida del soporte estructural normal del LCCr.

El objetivo de la cirugía no es «reparar» el propio LCCr. Debido a influencias biológicas y mecánicas, el LCCr no tiene capacidad para curarse una vez que comienza el desgarro, independientemente del grado de gravedad. A diferencia de lo que ocurre en la cirugía del LCA humano, el LCCr canino no suele «sustituirse» por un injerto. Este hecho se debe en gran medida a las grandes diferencias mecánicas que existen entre las rodillas bípedas (humanas) y cuadrúpedas (caninas), que hacen que las técnicas basadas en injertos sean menos fiables en los perros. Si se presenta de forma simultánea, el cirujano tratará la lesión de menisco extrayendo mediante cirugía las partes dañadas del menisco para estabilizar la rodilla. Algunos cirujanos pueden optar por realizar la liberación meniscal de un menisco intacto en el momento de la estabilización de la rodilla, para reducir el riesgo de futuras roturas de menisco latentes. Para tratar la inestabilidad de la rodilla, existen muchas opciones de tratamiento quirúrgico. Estas diferentes técnicas pueden clasificarse en dos grupos basados en diferentes conceptos quirúrgicos:

Las técnicas basadas en la osteotomía requieren un corte en el hueso (osteotomía), que modifica la forma en que los músculos cuádriceps actúan sobre la parte superior del hueso de la espinilla (meseta tibial). La estabilidad de la articulación de la rodilla se consigue sin sustituir el propio LCCr, sino modificando la biomecánica de la articulación de la rodilla. Esto puede conseguirse mediante el avance de la inserción del músculo (avance de la tuberosidad tibial [TTA]) o mediante la rotación de la meseta (pendiente) de la tibia (osteotomía de nivelación de la meseta tibial [TPLO]).

Las técnicas basadas en la osteotomía requieren un corte en el hueso (osteotomía), que modifica la forma en que los músculos cuádriceps actúan sobre la parte superior del hueso de la espinilla (meseta tibial). La estabilidad de la articulación de la rodilla se consigue sin sustituir el propio LCCr, sino modificando la biomecánica de la articulación de la rodilla. Esto puede conseguirse mediante el avance de la inserción del músculo (avance de la tuberosidad tibial [TTA]) o mediante la rotación de la meseta (pendiente) de la tibia (osteotomía de nivelación de la meseta tibial [TPLO]). Muchos cirujanos prefieren estas técnicas para perros grandes y activos, mientras que otros las prefieren incluso para perros pequeños y gatos, debido a sus resultados uniformes incluso en los pacientes más atléticos y a la reducción de la tasa de formación de artritis:

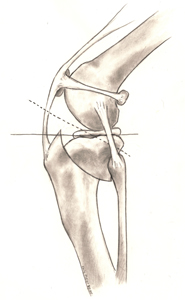

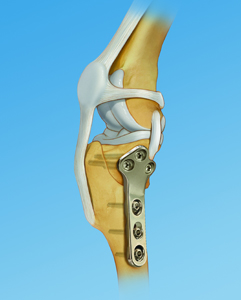

- La osteotomía de nivelación de la meseta tibial (TPLO) consiste en realizar un corte semicircular alrededor de la parte superior de la tibia y rotar su superficie de contacto (meseta tibial) hasta que alcance una orientación casi nivelada (aproximadamente 90 grados) en relación con la inserción de los músculos cuádriceps (Figura 2). Esto hace que la rodilla sea más estable en ausencia del LCCr. El corte en el hueso debe estabilizarse mediante el uso de una placa ósea de bloqueo y tornillos (Figura 3). Una vez que el hueso se ha consolidado, la placa ósea y los tornillos no son necesarios, pero rara vez se retiran a menos que exista un problema asociado (irritación o infección). Las ventajas percibidas en comparación con las técnicas basadas en suturas son los resultados superiores obtenidos en perros pequeños y grandes en relación con la función de las extremidades y la movilidad atlética, con una menor progresión de la artritis. El mayor inconveniente es la necesidad de realizar una osteotomía. Cualquier osteotomía requiere la consolidación del hueso y, si se observa algún problema (como el fallo del implante o la falta de consolidación del hueso), puede requerir una cirugía de revisión que puede afectar negativamente a los resultados a corto y largo plazo. Afortunadamente, este tipo de complicaciones son poco frecuentes, sobre todo cuando la intervención la realiza un cirujano con experiencia y certificado, y se respetan las restricciones de actividad postoperatoria.

- El avance de la tuberosidad tibial (TTA) requiere un corte lineal a lo largo de la parte anterior del hueso de la espinilla (tibia). La parte anterior de la tibia, denominada «tuberosidad tibial», se avanza hasta que la inserción del cuádriceps se orienta aproximadamente 90 grados con respecto a la meseta tibial (Figura 4). Esta es otra forma de conseguir la misma ventaja mecánica que ofrece la TPLO, que hace que la rodilla sea más estable en ausencia del LCCr. El TTA y la TPLO comparten ventajas e inconvenientes similares. De forma similar a la TPLO, el corte en el hueso se estabiliza mediante el uso de una placa ósea puente y tornillos específicamente diseñados. La decisión entre TPLO y TTA se basa exclusivamente en la opinión de su cirujano y en su experiencia técnica personal. Sin embargo, en un ensayo clínico prospectivo reciente en el que se comparaban perros con CrCLD tratados con TPLO, TTA o sutura extracapsular (ECR) con perros normales (con LCCr intacto), se demostró que la TPLO era superior al TTA y la ECR. Solo los perros que se habían sometido a TPLO tenían un paso y un trote un año después de la cirugía similares al de los perros normales mediante el análisis de la marcha con placa de fuerza.

- La osteotomía de nivelación basada en CORA (CBLO, por sus siglas en inglés) es una técnica más reciente y consiste en realizar una osteotomía tibial sin cortar la superficie articular. De forma similar a la TPLO, se utiliza una osteotomía de corte radial para nivelar la meseta tibial. Una ventaja de este tipo de osteotomía tibial es la posibilidad de realizarla en animales inmaduros con fisis abiertas (placas de crecimiento

Las técnicas basadas en suturas pueden dividirse en procedimientos intraarticulares (dentro de la articulación) y extraarticulares (fuera de la articulación). Debido a la falta de uniformidad de los resultados comunicados con las técnicas intraarticulares en perros, los procedimientos basados en suturas se realizan principalmente de forma extraarticular. La técnica que se realiza con más frecuencia se denomina estabilización con sutura extracapsular, que utiliza material de sutura que se coloca justo en la parte exterior de la articulación de la rodilla (pero debajo de la piel) para imitar la estabilidad que ofrece el LCCr. Una variante de esta técnica se denomina Tightrope® y permite a los cirujanos utilizar túneles óseos para la correcta colocación de las suturas.

- La estabilización con sutura extracapsular (también denominada «sutura Ex-Cap», «estabilización con sutura fabelar lateral» y «técnica del hilo de pescar») es una técnica muy utilizada. Aunque existen muchas variaciones de esta técnica, de material de sutura utilizado y de tipos de implantes de fijación, el objetivo constante es «imitar» la función del LCCr roto con una sutura colocada en una orientación similar a la del ligamento original. El objetivo a largo plazo es facilitar la formación de tejido cicatricial organizado periarticular (alrededor de la articulación) que proporcione estabilidad incluso cuando la sutura se estire o se rompa gradualmente. Las complicaciones más frecuentes tras este procedimiento son el fallo de la sutura y la aparición progresiva de la artritis. Los principales factores de riesgo de complicaciones con las técnicas basadas en suturas son el tamaño y la edad del paciente; además, los pacientes de mayor tamaño y más jóvenes presentan más complicaciones. Por estas razones, muchos cirujanos reservan las técnicas de sutura para perros de razas pequeñas, mayores y/o inactivos. Las principales ventajas de esta técnica son su coste normalmente más bajo, la falta de formación especializada necesaria para realizarla y la ausencia de incisión ósea. Debido a su capacidad para limitar la inestabilidad rotacional, en ocasiones se utiliza como procedimiento complementario de las osteotomías tibiales.

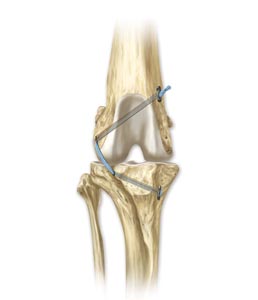

- La Tightrope® es una novedosa técnica de «sutura» desarrollada como alternativa a las técnicas basadas en la osteotomía. Utiliza un implante de sutura Toggle específicamente desarrollado, que requiere la perforación de orificios a través de los huesos del muslo (fémur) y de la espinilla (tibia) para una colocación anatómica más precisa del implante (Figura 5).Las ventajas de este procedimiento sobre otras técnicas basadas en suturas incluyen una colocación más precisa del implante y una mayor resistencia de la «sutura». En un estudio en el que se comparaban las técnicas TPLO y Tightrope® no se encontraron diferencias significativas entre ellas en cuanto a los resultados a los 6 meses de la intervención. Desafortunadamente, el uso de una sutura multifilamento en esta técnica puede dar lugar a una mayor posibilidad de infección y a un mayor riesgo de retirada del implante en el futuro, y en un estudio transversal reciente en el que se evaluaron las respuestas a una encuesta de cirujanos ortopédicos, se demostró que el procedimiento Tightrope® se percibía como el que presentaba el mayor índice de complicaciones en comparación con la TPLO, el TTA y la colocación de suturas extracapsulares.

El tratamiento no quirúrgico suele consistir en una combinación de analgésicos, modificación del ejercicio, suplementos articulares, rehabilitación física y, posiblemente, ortesis.

- Restricción de la actividad y antiinflamatorios: Aunque la administración de analgésicos a perros con CrCLD puede mejorar su bienestar, el dolor de rodilla perdura debido a la inestabilidad persistente de la rodilla presente y a la posible rotura de menisco secundaria. Por este motivo, las restricciones estrictas de la actividad (por ejemplo, las actividades con correa) suelen ser las más eficaces para reducir el dolor en los perros con CrCLD. Por lo general, este tratamiento se limita a determinados perros en los que no se puede realizar una intervención quirúrgica (p. ej., por limitaciones económicas, enfermedad, etc.), en cuyo caso también se debe considerar la ortesis.

- Rehabilitación: Está sobradamente demostrado que el tratamiento que aplica un veterinario debidamente formado en rehabilitación física puede acelerar e incluso mejorar la recuperación tras una intervención quirúrgica. Sin embargo, hay pocas pruebas que demuestren que se trata de una alternativa uniforme y predecible respecto al tratamiento quirúrgico de la CrCLD en perros.

- Ortesis de rodilla a medida: La ortesis de rodilla a medida es relativamente nueva en la ortopedia canina y en un estudio comparativo sobre la satisfacción de los propietarios entre la ortesis de rodilla a medida y la TPLO para el tratamiento de la enfermedad del ligamento cruzado craneal en perros, los resultados indicaron altos índices de satisfacción de los propietarios con ambas intervenciones. Dicho esto, las úlceras por vendaje, la cojera persistente, la intolerancia del paciente a la ortesis y la necesidad de cirugía posterior eran posibles complicaciones del uso de una ortesis.

- Gran parte del interés por las ortesis de rodilla para perros se basa en el resultado satisfactorio de su uso en humanos con lesiones del LCA. Sin embargo, la mecánica de la rodilla canina y humana son muy diferentes, y no es prudente hacer comparaciones entre ellas en relación con las modalidades de tratamiento. En este momento, no hay pruebas suficientes para apoyar ninguna recomendación de la ortesis de rodilla como tratamiento igual al de la intervención quirúrgica para la CrCLD, pero puede probarse para mejorar la función general si la cirugía no es una opción.

- Inyecciones intraarticulares: Existen varias opciones de tratamientos inyectables para intentar tratar la lesión del ligamento cruzado.

El plasma rico en plaquetas (PRP, por sus siglas en inglés) o el plasma autólogo condicionado (ACP, por sus siglas en inglés) son hemoderivados especializados que se obtienen mediante la concentración de las plaquetas del propio paciente. Las plaquetas concentradas pueden utilizarse como complemento de los factores de crecimiento del propio paciente para mejorar el reclutamiento de células en una zona lesionada. El PRP y el ACP son productos que se utilizan con éxito para ayudar a tratar lesiones ortopédicas en medicina humana y veterinaria. La posible opción de utilizar las plaquetas del propio paciente («autólogas») para ayudar a tratar esta enfermedad tan común y debilitante es un avance bienvenido para veterinarios y clientes.

La inyección intraarticular de micropartículas biocompatibles es un novedoso producto veterinario que está compuesto por partículas de colágeno y elastina, y se administra mediante inyección para ayudar a proteger el cartílago de la destrucción mecánica. El uso previo de este producto indicó un posible beneficio cuando se utiliza en perros con lesiones del ligamento cruzado y artritis en la rodilla. Se ha demostrado que mejora el bienestar y reduce los síntomas de cojera.

Los cuidados postoperatorios en casa son fundamentales. Las actividades prematuras, incontroladas o excesivas entrañan el riesgo de fracaso total o parcial de cualquier reparación quirúrgica. Dichos fallos, incluidos, entre otros, la fractura de la tibia o el fallo del implante, pueden requerir una intervención quirúrgica de gran envergadura. El cirujano de su perro le explicará detalladamente los cuidados postoperatorios adecuados antes y después de la cirugía.

Los estudios demuestran que la rehabilitación física puede acelerar la recuperación del perro y mejorar los resultados finales, independientemente de la técnica quirúrgica elegida. Esta rehabilitación debe comenzar inmediatamente después de la operación y suele incluir un régimen de amplitud de movimiento pasivo, ejercicios de equilibrio, paseos controlados con correa, etc. Los detalles adicionales deben comentarse con un cirujano certificado y/o un veterinario de atención primaria.

El pronóstico a largo plazo de los animales sometidos a reparación quirúrgica de la CCLD es bueno, con informes de mejoría significativa en el 85-90 % de los casos. Aunque la artritis puede progresar a lo largo de los años independientemente del tipo de tratamiento, se espera que sea más lenta cuando se realiza una intervención quirúrgica en comparación con el tratamiento médico. Por lo tanto, se recomienda el tratamiento multimodal de la artrosis para cualquier perro con CrCLD, independientemente del tratamiento. Debe consultar con el cirujano y/o el veterinario de atención primaria de su perro las posibles implicaciones de este tratamiento.

La obesidad en los animales de compañía lleva asociados numerosos problemas de salud adicionales a la CrCLD. La pérdida de peso debe considerarse fundamental para las mascotas con sobrepeso y CrCLD. Su veterinario puede ayudarle a determinar el peso ideal de su mascota y la mejor forma de alcanzarlo.