Tracheal collapse is a chronic, progressive, irreversible disease of the trachea, or windpipe, and lower airways (mainstem bronchi collapse). The trachea is a flexible tube and, similar to a vacuum cleaner hose. It has small rings of cartilage that help keep the airway open when the dog is breathing, moving or coughing. The rings of cartilage are C-shaped, with the open part of the C facing upward. In some dogs, the C-shaped cartilage becomes weak and begins to flatten out. As the roof of the trachea stretches, the cartilage rings get flatter and flatter until the trachea collapses (Figure 1). The collapse can extend all the way into the bronchi (the tubes that feed air into the lungs), resulting in severe airway compromise in your pet.

Small breed dogs are most commonly affected with the disease, particularly Yorkshire terriers, Pomeranians, Poodles and Chihuahuas. Affected dogs are often middle aged or older, though it can be seen in some young dogs as well. Dogs that are overweight or that live in a household with smokers may be more at risk or at least more likely to show clinical signs.

- harsh dry cough that sounds like a goose honking

- coughing when picked up or if someone pulls on their collar

- difficulty breathing

- exercise intolerance

- coughing or turning blue when excited

- fainting

- wheezy noise when they breathe inward

In general, the following tests are recommended to diagnose the degree of collapse, provide a clear picture of overall health and evaluate your pet:

- bloodwork to look at overall health

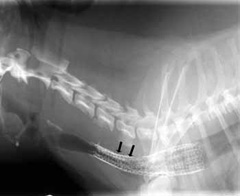

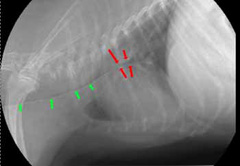

- chest x-rays (Figure 2, 3) may help with the diagnosis in some pets, and are useful for ruling out other conditions and looking at the size of the heart. Tracheal collapse is not always visible on regular x-rays.

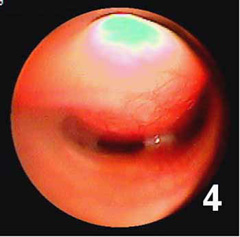

- fluoroscopy (a moving x-ray) ̶ this will allow a check of the condition of your dog’s trachea when he/she is breathing in and out (Figure 4). This is important since the size of the trachea can change depending on if your dog is breathing in or out.

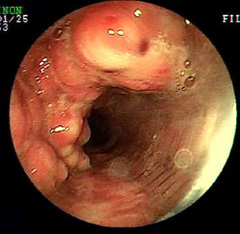

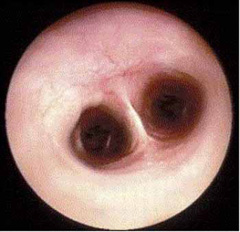

- endoscopy (viewing the inside of the trachea with a fiber optic camera) provides the best detail of the inside of the airway (Figure 5) and allows your veterinarian to take fluid samples for culture and analysis

- echocardiogram (an ultrasound of the heart) ̶ to evaluate cardiac function

Medical Management

Medical management includes:

- weight loss

- medications to reduce airway spasms and inflammation

- sedation to reduce coughing and anxiety

Some dogs may require heavy doses of sedation to break the coughing cycle, since coughing will irritate the airway and lead to more coughing. Additionally, dogs should be kept away from smoke and other environmental pollution (coughing may be even stimulated by smoke or other irritants brought in on clothing and hair). Dogs with infections are treated with antibiotics.

Medical management may work for up to 70% of dogs, particularly those that have mild collapse. As the disease progresses, some pets do not respond to medical management, and require surgical or interventional treatment. Medical management will need to be continued for life, even after other interventions.

Surgical Management

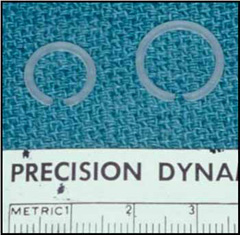

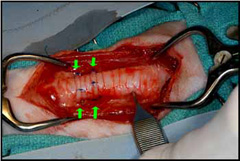

Collapse of the trachea in the neck may be treated by an ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon surgically placing plastic rings (Figure 6, Figure 7) or spirals around the outside of the trachea.

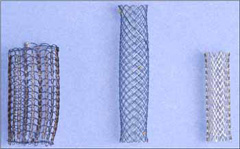

Tracheal collapse may also be treated by placing a stent ̶ a spring like device ̶ inside the airway to hold the trachea open (Figure 8). Stents allow treatment of tracheal collapse in the neck or within the chest without a surgical incision.

Most pets are discharged 1–2 days after surgery. They are usually returned for recheck and removal of skin sutures or staples (if present). Pain can be well-controlled with owner-administered medications.

Recommendations following ring or stent placement include:

- continued medical management with medications to decrease pain, swelling, coughing and excitement

- use of a body harness (not a neck lead or leash)

- limited activity for about two weeks to allow recovery and incision healing

- weight loss

- avoiding exposure to smoke or other airway irritants

- use of a humidifier in the winter when heaters are used

- regular follow-up examinations by your primary care veterinarian

Post-treatment complications can include:

- Surgery to place rings around the trachea may result in coughing, bleeding, airway damage, or paralysis of the larynx. Dogs that have a paralyzed larynx may require emergency surgery to tie open the airway or to temporarily allow breathing through a hole in the neck (“tracheostomy”), and some may die immediately after surgery.

- Many dogs will continue to cough for the rest of their lives, though the cough is usually milder than before treatment.

- Some dogs will continue to have clinical signs if collapse of the airway progresses into the smaller airways (bronchial collapse).

- Stents placed in the airway can also contribute to irritation and coughing. If enough inflammation occurs, the dogs can develop thick tissue in front of or behind the stent that blocks part of the airway (Figure 9).

- Stents that span the thoracic inlet, where the trachea enters the chest, are at risk of breaking due to movement of this area (Figure 10).

- Stents that are too small can move within the trachea.

At this time there is no known prevention for tracheal collapse, although reducing weight or exposure to airway irritants such as smoke may help. About 70% of dogs that are treated with medical management alone will show some improvement. About 75% of dogs improve after surgical placement of rings. Dogs that are older than 6 years of age or that have laryngeal or bronchial disease have more complications and a poorer long-term outcome. Of dogs that receive stents, 95% are immediately improved and 90% are markedly improved on their follow-up visit. Similar results are reported with rings placed in the cervical (neck) region of the trachea. Control of coughing is important for a good outcome, and dogs with bronchial collapse (and therefore continued coughing) are much more likely to have problems after stent or ring placement.